Carrie’s Song at GooglePlay Books (Ebook)

Carrie’s Song Audio book at GooglePlay Books

Buy Carrie’s Song here (D2D various ebook outlets)

Carrie’s Song (paper back at Amazon)

Carrie’s Song (Amazon’s Kindle)

Carrie’s Song Print Book At Amazon

Finalist in African American Fiction at Next Generation Indie Book Awards

Accolades for Carrie’s Song:

“Carrie’s Song is a delightful episodic tale of American history in the 1800s, as told from the point of view of a young African-American woman who was passionate about music and teaching, and who participated actively in campaigns in favor of the right to vote for women and against lynching. Bright and well-educated, Carrie eschewed the proscribed life of domesticity that was expected of her. She wanted much more. That Carrie Crawford was the author’s great grandmother, and she is portrayed with a certain wonder and reverence. Taylor also demonstrates facility in capturing the well-researched details of the time and milieu.”

— Saralyn Richard — author of Murder of Principal and Bad Blood Sisters — 2021 First Place Mystery/Suspense Novel in Speak Up Radio Contest, and other notable awards.

Carrie’s Song Summary

Step into the vibrant and tumultuous world of Carrie’s Song, a gripping tale set against the backdrop of 1890s Nashville, where the echoes of slavery still reverberate, and the fight for justice and equality hangs in the balance. In this captivating narrative, Carrie, a determined and resilient woman, navigates a life fraught with danger and obstacles as she strives to graduate from Fisk University, a mere three decades after the shackles of slavery were broken.

The narrative unfolds with a chilling blend of murder, attempted rape, and knife-wielding thugs, forcing Carrie to confront not only the personal challenges of her education but also the harsh realities of a society grappling with its own demons. Fueled by a passion for justice, Carrie becomes a fearless foot soldier in the battle against the heinous lynching of people of color, and a staunch advocate for women’s right to vote. Her journey takes her through the heart of one of the most volatile periods in U.S. history, where societal upheavals mirror the tempest within her own soul.

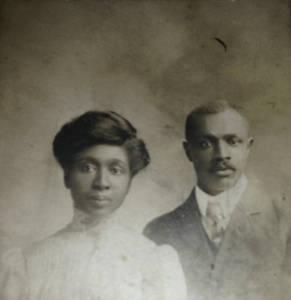

Amidst the chaos, Carrie finds solace and expression in her love for music. As she skillfully plays the piano and violin, her melodies become a testament to resilience and a call for change. However, her budding romance with Edward adds another layer of complexity, as he embarks on a perilous journey to the Spanish American War. Their love story becomes entwined with the larger tapestry of historical events, creating a poignant and deeply moving narrative that captures the essence of an era marked by struggle, courage, and the pursuit of a brighter future.

Carrie’s Song is not just a historical novel; it’s a symphony of emotions, a tribute to the indomitable human spirit, and a riveting exploration of love, justice, and the unyielding power of music in the face of adversity. Join Carrie on her extraordinary journey, where every note played and every step taken contributes to a timeless melody of hope, resilience, and the unwavering pursuit of a better world.

The next book in the Flight of the Heart series is The Music They Made.

To receive Dale’s newsletters, write to her at Dale Marie at dmarietaylor@gmail.com

Sample Chapter from Carrie’s Song

Preface

Men grabbed him by his shoulders and shook him. “You will hang,” one of them said. “You will know the pain. You will understand that you can’t do as you please.” They were seated on horses, all of them, their faces covered with masks. He’d tried to outrun them, but it was useless. There were too many of them. Sam did not bother to speak. He knew it was pointless. His hands were tied behind his back. He had sent his wife and his children far away, having anticipated this event. One of the men threw a rope over the branch of a tall tree and made a loop.

Another cleared his throat as though he wanted to speak. His eyes darted around as though he were afraid of his companions. Finally, he croaked out, “Hey, Jim, ain’t this here a white man?” Jim glared at the offending questioner but said nothing.

The horse under Samuel skittered and tried to shy to the right as the men prepared the hangman’s noose. He sighed as he prayed for deliverance. To have come so far. So much done, but now, his land and his property were in the hands of these thieves. Little did they know that he had outsmarted them. Sam had seen the trouble brewing in the little community where he lived. These same men had thrown rocks through the door of his dry goods and hat shop. They did not know that he had wealth hidden and that he had arranged for his family to escape with some of it. When the noose tightened around his neck, he thought of his wife’s sweet face and her beautiful singing voice. Those were his last thoughts as the men slapped his horse and the noose cut into his neck.

CHAPTER ONE

1896

Carrie ran her fingers over the yellowed keys of the piano, easily playing her favorite Beethoven composition. She continued playing one piece after another – Chopin, Mozart, Brahms and Schubert – from memory, while her mother, Emma, grandmother, Caroline, and Miss Esther chatted quietly and drank tea. Carrie wore a blue wool dress, tied in the back with a ribbon. Her hair was pulled up into a Gibson Girl hair style with the front of her hair pulled into a tight roll. Her delicate brown fingers flew across the keys.

Emma, Carrie’s mother, dressed in a gray wool dress that allowed for the growth of the baby she carried. The empire waist was fitted just under the bodice. Her grandmother, Caroline, dressed in a black wool dress with gray lace adorning it. Her grandmother was heavy chested, so the dress accommodated her fuller figure.

Carrie, her mother, Emma and her grandmother, Caroline made regular visits to see Miss Esther, who had lost interest in playing the piano or working in her garden since the Civil War. Esther, the white half-sister to Carrie’s grandmother, Caroline, had given Emma sheet music and a newer piano, while keeping the older one at her own home for visits just like this one.

Carrie was to play while they visited; Carrie’s brow wrinkled as she had another of those visions. This time, it was of Esther, her grandmother’s sister. She took a deep breath and willed the image away so that she could continue to play. To distract herself, Carrie focused on the recent argument she’d had with her mother.

It was 30 years after slavery had ended and Carrie’s grandmother, Caroline, had married Esther’s family friend, Samuel. But, in 1896, it really should not matter, Carrie thought. Things were changing.

Carrie’s family should not be friendly with Esther and should not play a servant’s role. Carrie wanted more than was implied by Booker T. Washington, who urged all Negroes to learn a trade, domestic for women and menial labor for men. She wanted to graduate from Fisk University.

It would be a first for her family. Just 30 some odd years after slavery ended – she would be the first in her family to earn a college degree. But would she be able to do it? No one seemed to take her seriously. Her mother wanted to her to learn to do housework – to wash clothes, to tend to babies, to clean houses. But she wanted to play music. Her heart was in the music.

The pressures were mounting. She taught school to be certain that she contributed to the household; also, it was just necessary. Her father would tolerate her impractical notions about playing music if she made money as a teacher.

It was a good thing to do – teaching. So many Negroes hungered to learn to read, write and cipher. She sighed. Working and trying to get her college degree at the same time was tiring. But it had to be done. Could she do it? Could she graduate? Would there be obstacles in her way?

Carrie felt there should be more to life than domestic work. After all, her grandmother had been enslaved — their lives had been nothing but domestic work. It was time for a new day. But it seemed she was trapped in expectations of the day. The argument she’d had with her mother just an hour ago reverberated through her as she played.

“I don’t want to be a domestic worker,” Carrie said quietly. “I want to graduate from Fisk, study, play music, travel. I want to see the world, to teach students to love music and poetry. I want to see art and to create it. Why can’t I do those things?”

“Because, dear, we must know our place in time,” Emma said, sighing as she poured water into the sink of the little kitchen. Carrie cringed and turned her back on her mother. She felt a little guilty as her mother was several months pregnant and she did not want to upset her. Her mother was too fond of taking a conservative viewpoint, like the famed Booker T. Washington.

They had left the argument where it was to make their Sunday visit to Esther, her grandmother’s half-sister, who was now unable to hear well or to do for herself. The women always brought her prepared food and a little something more from their garden.

Esther thought of her life before things became so different, before slavery ended, as she looked at Caroline, her half-sister. She wondered what had happened to Caroline’s husband, Samuel. Something deep and tender moved within her as she spied on her sister’s grandchild, Carrie. Samuel, who had been a friend of Esther’s family, would be so proud.

The emotions were so profound that she found herself wanting to touch her grand niece’s beautiful dark skin, to listen to her sing, to spend hours talking with her. The rivalry that darkened relationships between half-sisters born during slavery was not there for Caroline and Esther. Thus, Esther saw Carrie as a niece. This was not a good time to make their relationship clear as Caroline was mulatta.

Esther’s childhood with Caroline was fraught with tension and secrets; Caroline was Esther’s only sibling. Esther remembered her tendency to wait on her younger sister, something that disturbed visitors who came to see the family.

Their playful girl games — having tea, running through the fields after butterflies and tossing a ball — gave them endless hours of happiness. They shared so much in the way of looks; if it had not been for Caroline’s olive skin, they might have been twins.

Caroline and Esther never knew that there was a difference between them since their father treated both girls well. The war was not over when their father, Robert, became ill.

His wife had died when Esther was born, so Caroline’s mother, Ella, cared for the two girls as though both were her own. It was for that reason that when Caroline became of age, the neighbors were pleased to see Samuel showing an interest in her.

The Africans who lived in the neighborhood whispered of the family’s dotage on Caroline — of her pleasant but seemingly prissy exterior. To them it seemed ingenuine, but that was truly who Caroline was — the protected and loved daughter of a doting father.

Many people thought the relationship was odd, but they were not the only family that hid their esteem for family members who were a little darker, a little different. Where they existed, they were a closely guarded secret. As long as the European and African family lived an otherwise unblemished life, living separate lives, in separate quarters at least outwardly, they could live unharried.

Esther tried to talk her sister out of marriage to Samuel, but Caroline was happy that someone showed an interest in her. It seemed that nobody would. Her light brown skin and European features marked her as a mixed child.

Since Caroline was so deeply loved by her sister and father, no one dared suggest she attend the social events hosted for young girls of African descent. Esther monopolized Caroline’s attention. Neither girl had much of a social life outside of the home, and as they grew into their late teens, it became evident that they might become spinsters.

Neither might have cared since they spent their time in the company of one another just as they had as children, reading, playing music and sewing. Both girls were educated at home by their father and by trusted tutors. However, Caroline was always cautioned to hide her education. The vast home library kept them busy for hours. When Sam began to call on Caroline, Esther realized that she was headed toward an adult life without ever having been courted.

“Why do you need to be married at all?” argued Esther, glaring at her sister through eyeglasses and over the top of her book.

“I’ve told you for the last time, I want to find out what it’s like to be loved like that. It’s my decision,” Caroline said, returning the glare with a short glance. “You can marry too, Esther. What about that boy who came to the holiday party? He was surely interested in you, but you wouldn’t return his letters or notes or even go on a buggy ride with him.”

“I have more important things to think about,” Esther said. “Besides, if I go down that road, there’s no turning back. Once you begin, your destiny is fixed with children and familial obligations. I want to write and read and continue my collection of butterflies. If I stop to get married, I won’t be able to do that. Besides, I haven’t met the man who’s going to let me have my way. When I do, maybe I’ll consider a buggy ride.” She leaned over her book and stuck out her tongue at her younger sister, widening her eyes as she said, “buggy.”

“Esther, you’re so impossible. You’re one of the prettiest girls in the county, yet you hold yourself so aloof. You know what Andrew Marvell would say.”

“Yes, seize the day, but why should I when I have you to do it for me?” she winked at Caroline, and they never returned to the subject. But when Caroline was ready for her big day, Esther did all she could to make the affair a special occasion.

Esther found a way for Caroline and Sam to have a real marriage like any other couple. It could be done if the antecedents were hidden, which Esther arranged through friends. Esther baked a cake and invited their close friends to the house for a reception. Though Ella was ill and near the end of her days, she too made an appearance for the couple’s reception. The young people chatted, played cards, and whispered to each other. When everyone went home, Ella pulled Caroline aside a pressed an ancient shekel coin into her hand. She smiled at her daughter and said nothing more. Caroline knew what to do with the coin.

William rubbed down the horses that had brought them to Esther’s house. The days were getting shorter and the weather chilly. He thought about his origins and wondered why his mother insisted on visiting Esther. William and his mother came from East Tennessee to Nashville following the disappearance of his father, Sam.

William took pride in the idea that he had opened his first bank account at a penny savings bank and began building his business. Soon, William and Emma married, she at 16 and he at 21, and they began to have children. Carrie came first, then Willella. William stood outside the house where his mother’s sister lived, waiting for the women to finish their visit.

He could not abide visits to Esther’s house. Slavery had not been over long when Esther was insisting that his mother come visit. He was just a boy then, but he had to come along.

People around here did not like this kind of friendship. It made William nervous. The women seemed to be determined to live dangerously. William shook his head and walked the horses to the back stables where Abner was tending to the livestock.

“Will,” Abner said, nodding. “The women folks up at the house visiting?” William nodded. He led the four horses to the trough to drink and unhooked them from their traces.

“No telling how long they gonna be,” William said. “Might as well make the horses comfortable.” Abner nodded and walked over to where William was preparing to unhook the horses so he could finish watering them and lead them out to a pasture.

“What you been doing lately, Abner?” William asked.

“Nothing but tending to things for Miss Esther, that’s all,” Abner said. “She got some notion in her head she want to go into town from time to time. So’s I drive her.”

“That’s good, good,” William said. “What about that woman you was seeing when we last came over here, what’s her name?”

“Johanna,” Abner said. “We got married, one on the way.” Abner grinned.

“Congratulations, Abner,” William said, smiling. Abner pointed to the back of the barn where there was a path leading to his home.

“Come on over,” Abner said. “Johanna always got some victuals on the stove.” William wasn’t hungry, but he agreed to visit with the couple while his mother, wife and daughter visited with Esther.

Caroline was pleased to find that her son, William, and her grandchildren had hope. William stood outside of the house with the horses rested, fed and watered. He helped Caroline down the steps of Esther’s house. Esther did not look as good as Caroline had hoped. The lung problems were back. She knew it. But Esther was not one to complain.

“You look happy, William,” Caroline said. “Unlike your daughter who has been out of sorts the whole time I’ve been visiting my sister.”

William frowned and looked at Carrie as if to say, This is not like you. Carrie held her head down and her skirts up as she skipped down the steps. But suddenly, she turned about, ran to Esther and took her hand. “Be careful going up and down steps,” Carrie whispered, smiled tightly and squeezed the older woman’s hand gently.

Carrie stood there a moment looking into Esther’s rheumy brown eyes, then turned away and bounced down the steps again. With her father’s help, she climbed atop the carriage to sit with him. William motioned for Emma to remain on the porch while he helped his mother, Caroline, into the Brougham.

Then, he raced up the steps and helped Emma as well. He handed Emma into the carriage and waited for the ladies to say they were ready to depart. Emma placed a hand on her large stomach, smiling as she felt the baby kick.

Esther stood on the porch, holding a handkerchief in the air as she waved to her sister and her sister’s family. All of Esther’s family was gone. The war had taken some; others had been felled by disease. Caroline and William were all Esther had.

Caroline’s son and daughter-in-law were doing what they could among the throngs of other Coloreds who were fighting to make a living in Nashville.

It worried Caroline that lynching was not challenged and that William or even one of her granddaughters might be a victim of the hatred that boiled up after the war ended. But she had to focus her attention on feeding her family and being certain they were well.

As the carriage ambled along toward Nashville, Carrie peered ahead. She frowned as she saw a gathering of whites around a little church. Colored people were arguing with the whites. The little church was ablaze and had been set on fire by the whites.

Carrie nudged her father’s arm. “Papa, hang back a while,” she said. Carrie sat on the bench seat with her father, hoping that the noise did not mean trouble for her family, but knowing that it certainly did for the Blacks who were gathered ahead.

Another of those headaches had pinched behind her eyes. This time a sense of dread accompanied it so that she wanted her father to wait. William pulled the horses back and to the side of the road, well away from a throng of white people who waved torches and shouted at the Colored folks. Her grandmother stuck her head out and motioned to Carrie.

“Carrie-girl, you come on down from there and wait inside the carriage,” her grandmother said. Her father helped Carrie get down from the bench seat and helped her into the carriage with his mother and wife.

A trickle of whites appeared to attempt to subdue the rowdy white group and to help put the fire out.

The Colored church members raced back and forth to a little creek carrying water to fight the fire that was attempting to engulf the little church. After Carrie was settled, her grandmother peeked out the side of the carriage and motioned to her son.

“William,” Caroline said. “Be careful.” William nodded and went to find out how he could help. The little church had been painted white and had been built in a clearing. It was not larger than 500 square feet with a small porch and plain windows on the side. The roughhewn boards suggested that the parish members might have built the church from nearby trees.

Many of the Colored men were dressed in their Sunday best of black pantaloons and a white shirt. Their women folk, some of them dressed in dark wool dresses and others in colorful greens and blues, hung back some distance with children clutched tightly to them.

Some were discarding overcoats as the fire grew more intense. Though it was a damp late spring day, the cool weather did not seem to help keep the fire contained.

“What happened here?” William asked as he helped carry buckets of water from a creek to the church. An old black man spit and looked sharply at William.

“You from the city, ain’t you?” the old man said. William nodded as he splashed water on the building.

“These here folks don’t want us to be learnin’ our childrens,” the old man said. “They’s trying to burn down our church cause that’s whar we learnin’ the children how to read and write.” William frowned as he saw some whites standing about and cursing at the increasing numbers of Blacks and whites who came to help put out the fire.

“They cain’t stop you if you don’t let ‘em,” William said.

“You right ’bout that, young man,” the old man said. “And thank ya kindly for stopping to help.” William nodded. He went to the carriage to tell his mother, wife and daughter what had happened and to get some of the cool tea his mother had brought along for the trip.

In about an hour, more people, white and Black, showed up to help put the fire out and to help the Black church members bring out benches and pews.

The church entrance was badly burned, but much of the building had been saved. William shook hands with the men of the church and walked the half mile back to the carriage where his family waited. He climbed on top of the carriage. His mother was tired and irritable. It was time to get them home. After they had passed the church, Carrie knocked on the top of the Carriage roof. William knew what that meant. She wanted to rejoin him on the bench seat.

William’s thoughts turned to the ways he and Emma had struggled to make certain that Carrie had a good education. He maneuvered the carriage around a large pothole and clucked to the horses. The days were turning cooler as fall was near.

“Papa,” Carrie said. It was more like a question. He knew that Carrie had questions.

“Why were those white people trying so hard to keep those Colored people from having a church?”

He explained that the church members were also attempting to teach their children.

“Why don’t they just move to Nashville where there are public schools?” Carrie asked.

“Carrie-girl, when it was time for your schoolin’, me and your Mama decided to send you to the school for Colored children, one new for the education of the children of slaves.”

“But I know that many of the people who come to my school to learn to read and write are much older than they should be,” Carrie said. “It’s like they never had a chance.”

“That’s right,” her father said. “Colored people be punished if they try to learn readin’ and writtin’ because if they know how to do that, they might find a way to escape.” Carrie sat there for a moment digesting that information. The sound of the horse’s clop clop in the dirt and the smell of clean earth filled the air. Her father flicked the reins gently on the backs of the horses to shoo away horse flies.

“Your grandmother’s sister, Esther, offer us to a tutor for you and Willella at the mansion, but your grandma want me and your mother to teach you as much as we could at own home first,” he said.

He explained that the Catholic Church had Sunday schools where many Colored people were taught to read and write. Caroline and her family were among those who benefited. From there, Caroline had hounded William to learn to read and write and be certain his family was educated too.

“Why did you and Mama know how to read and write?” Carrie asked.

“It’s a matter of holding yourself up, Carrie-girl,” her father said. “It was important to us that you know how to dress and how to act. Your Mama sewed clothes for you so you look neat and clean, and sometimes you were the only girl dressed good. We don’t know what we should. We learn a little bit here and there. You been showin’ us how to talk and I try, not always perfect, but I try.”

Her father said that in 1886, when Carrie was 8, his mother, Caroline, was among the elders that went to the city aldermen and asked that a high school be established for Negro children. Though Carrie was young then, her parents had high hopes that she would go quickly to the next level of her education.

Carrie remembered that when she had turned 10, she had excelled in arithmetic, writing and music. She was allowed to teach her peers. By the time she was 15, she had mastered the subjects that had been offered at the local school for Colored children — geometry, physical geography, civil government, English, Latin, physics, chemistry and ethics.

Children of the time were to demonstrate how well they could carry themselves in the hostile environment that was the Reconstruction era. They were to show whites that they could conduct themselves with decorum. Carrie’s grandmother knew that her granddaughter’s attitude was the result of the pressure of the times.

“I sometimes feel better talking to Grandmother Nana,” Carrie said. Her father nodded and clucked to the horses. The sky appeared cloudy as though it would rain. Carrie felt herself pulled between two forces of the time – one espoused by Booker T. Washington and the other by W.E.B. Dubois, who was an alum of her school, Fisk University.

She and her mother, Emma, often argued the subject behind the closed doors of their modest home at Jefferson Street. Caroline tried to keep the two women from getting too worked up.

When they returned home from their visit with Aunt Esther, William took care of the horses in the barn where he housed horses, carriages and wagons that he used in his coal delivery and transportation business.

Caroline could see that Carrie was getting worked up for another confrontation with her mother. Carrie felt compelled to press her point. Willella greeted her at the door to the back of the house. She was dressed like her sister.

Willella, Carrie’s sister, had stayed at home while the three women had visited Esther. Caroline, the elder Mrs. Crawford, sat beside Willella helping to prepare green beans for supper. Emma and Carrie picked up their argument right where they’d left off.

The kitchen smelled of stewed chicken, potatoes and greens. Willella changed her clothes and took a seat in a corner of the kitchen where she snapped off the ends of green beans and snapped them in half. She rolled her eyes at her older sister as she watched her mother and sister argue.

Though Emma was seven months pregnant, this did not slow her down. William came in from having seen to the horses. Two of his crew members for his business, Crawford Coal and Cabs, had stayed in the barn and were taking care of the horses and cleaning the carriage.

William had cleaned himself up and was trying to read a newspaper, as he often did. He tried to pretend that he did not hear his wife and daughter bickering.

“But mother,” Carrie continued. “This is a matter of conscience. It’s important to do what you think is right for yourself, not what others think you should do. I want to play the piano, teach, see the world, not work as a domestic. Isn’t that what you would do if you could?”

“Watch your mouth, young lady,” Emma said, putting her hands on her ample hips. “I want you to be happy, but it’s time you faced facts. Colored folks are struggling enough to get by. Not everybody can be a teacher. I’m proud of you for teaching at the school; I know you’re capable, but I’m just saying that you need to face facts. Try to do something more than just keep your head in them books … in the clouds. Learn how to sew, cook, clean. Be practical. Life may demand it.”

Buy Carrie’s Song here (D2D various ebook outlests)

Carrie’s Song (paper back at Amazon)

Carrie’s Song (Amazon’s Kindle)

Carrie’s Song and other books by Dale Marie Taylor are published by Narrativemagic Press. narrativemagic.com